The Sheffield, Ashton and Manchester (S.A.& M.) was a railway with ambition. Not that this was unusual in the 1840s - railways then either grew big or died. Although it had begun life in 1838 it only achieved its descriptive title in 1845 when the Woodhead Tunnel was completed, giving a through route to Sheffield. The following year it proposed a branch from Hyde to Whaley Bridge via Marple and backed that up by buying the Ashton, the Macclesfield and the Peak Forest Canals together with the Peak Forest Tramway. However, this was the high point of railway mania and the S.A.& M. did not have the finances to match its ambitions. It pulled up the short length of lines that had been laid and allowed its parliamentary authority to lapse. Worse followed. A competing railway was built to Whaley Bridge from Stockport via Disley - the S.D. & W.B. - opening in 1857 and passing through (but not stopping at) High Lane.

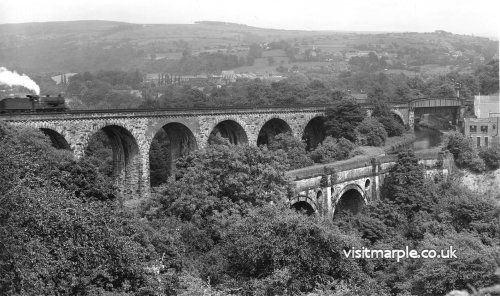

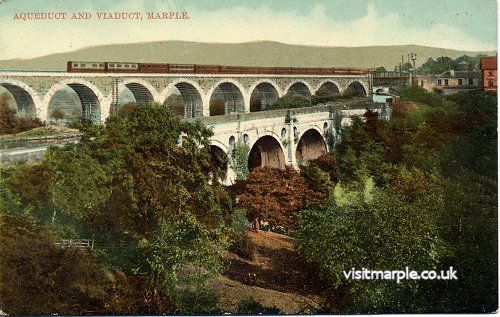

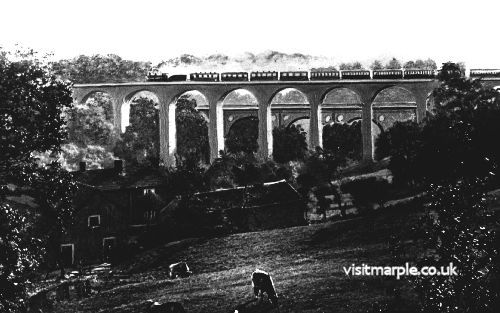

A steam train crosses Marple Viaduct, with Marple Aqueduct in the foreground.

By now S.A. & M. was in a slightly better financial state as it amalgamated with various small lines in Lincolnshire and became the Manchester Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway (M.S.L.). In 1858 it resurrected the old plans for a line to Whaley Bridge. A contract for £80,000 was signed to build a line from Hyde, via Woodley and Romiley, to “Compstall.” For the purposes of the contract “Compstall” was a temporary station high above the Goyt, near Marple Aqueduct. No trace remains of this station as it was a temporary wooden platform though there is a hollow on the south side of the cutting, just west of the viaduct which may have been the site.

The 1862 edition of Bradshaw shows seven trains each way between London Road and “Marple.” It does not explain that anyone thinking that they had arrived in Marple would have been sorely disappointed. Or for that matter, Compstall. The station was a long way from either. Using the same logic, Ryanair flies to an airport that it calls “Paris-Beauvais Tille”, 53 miles from the centre of Paris and to “Frankfurt-Hahn”, 70 miles from Frankfurt.

Obviously, “Compstall” was never intended to be the terminus, and in 1860 a bill was laid before Parliament for the Marple, New Mills and Hayfield Junction Railway (M.N.M. & H.J.). The engineering works required for this line were formidable; not the least of the problems lay right at the beginning of the route - a bridge over the Goyt valley. At that time the river was known as the Mersey; it was only in 1898 that the Ordnance Survey made a ruling that the Mersey began at the junction of the Goyt and the Tame in Stockport. The engineer for the line was J.G.Blackburne and the contractors for the Marple to New Mills section were Benton and Woodiwiss. Hundred of navvies were brought into the district as well as the more skilled carpenters, stone masons and bricklayers needed to build a railway line. It must have been similar to the time 60 years previously, when the Peak Forest Canal was constructed and masses of navvies flooded into the area, although by now Marple was a much more substantial township.

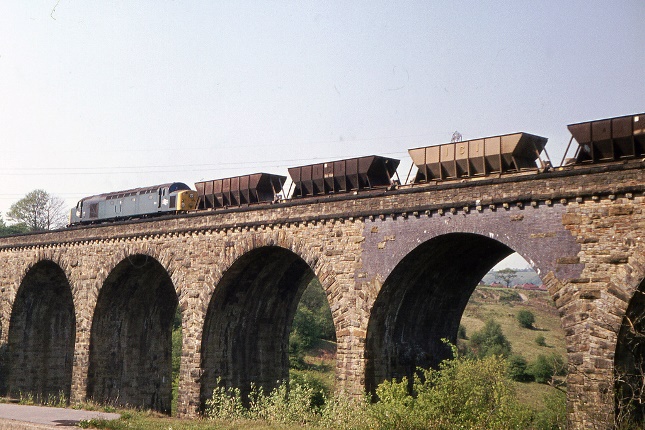

The first stone was laid on 24th September 1861 and the last arch was keyed in on 20th September 1862, in a formal ceremony in front of 6000 people. It opened for traffic about two months later. This was at the height of the cotton famine so was a welcome change from the prevailing circumstances. And what an achievement it was. It ran alongside and dwarfed the Marple Aqueduct which had been built sixty years before. It comprised thirteen stone arches together with a cast iron girder bridge, standing 124 feet above the river. In total it is 918 feet long and comprised 18,000 cubic yards of masonry. In comparison the aqueduct stands 90 feet above the river, is 315 feet long and comprises 8,000 cubic yards of masonry. Most tellingly of all it took little over a year to complete and no one was killed or badly injured whereas the aqueduct took six years to build and seven men lost their lives.

The first stone was laid on 24th September 1861 and the last arch was keyed in on 20th September 1862, in a formal ceremony in front of 6000 people. It opened for traffic about two months later. This was at the height of the cotton famine so was a welcome change from the prevailing circumstances. And what an achievement it was. It ran alongside and dwarfed the Marple Aqueduct which had been built sixty years before. It comprised thirteen stone arches together with a cast iron girder bridge, standing 124 feet above the river. In total it is 918 feet long and comprised 18,000 cubic yards of masonry. In comparison the aqueduct stands 90 feet above the river, is 315 feet long and comprises 8,000 cubic yards of masonry. Most tellingly of all it took little over a year to complete and no one was killed or badly injured whereas the aqueduct took six years to build and seven men lost their lives.

The cast iron section was required because the railway crossed the canal at an acute angle and this required a skew bridge. Normally in these circumstances with normal roads, one or other of the roadways would be altered so that one crossed the other at right angles. However, this was not possible with railways and canals as they both required a relatively straight course. Bridges built at an angle - askew - present a much more complex engineering challenge, particularly with masonry bridges. Construction requires precise stone cutting because the faces do not form right angles. Even though Benjamin Outram, the builder of the aqueduct, had mastered the basic principles of skew bridges in the 1790s, the mathematics and understanding of the forces involved had only been fully understood by the 1860s. A masonry skew arch could have been constructed but it needed skilled craftsmen and would have cost far more than an ordinary arch. At the same time, the technology of iron manufacture had made dramatic progress and quality was increasing whilst costs were coming down. An iron girder bridge supported on masonry abutments was both cheaper and quicker.

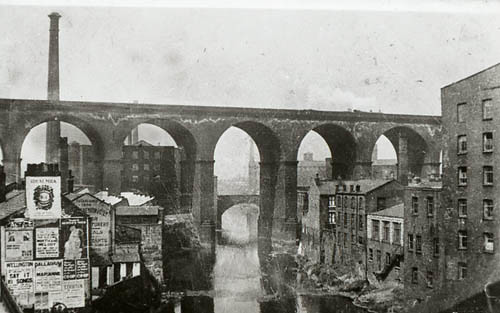

Edgley Viaduct |

Marple Viaduct |

Perhaps the best comparison for the viaduct is the Stockport Viaduct, or the Edgeley Viaduct as it was then known. That had been built 20 years previously in 1840 by a rival company, the Manchester and Birmingham Railway, It is much bigger, 1800 feet long and built entirely of brick, 11 million of them, though Marple does have the edge in being slightly higher - 124 feet compared with 111 feet. As a result the Stockport Viaduct is classed as Grade 2* by English Heritage whereas Marple only rates Grade 2. Nevertheless Marple can claim to be the more original structure as it is virtually unaltered since it was built whereas Stockport was doubled in width in the 1880s.

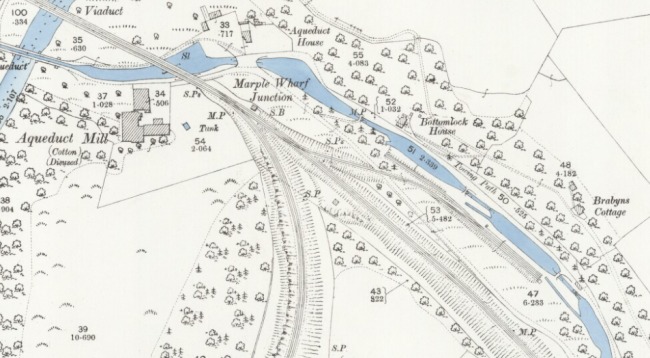

Although it now had a viaduct, Marple had to wait another three years before it had a railway. As soon as it was completed it was used to bring in materials to build the railway line. They were unloaded at what was planned to be a temporary terminus, Marple Wharf. Initially this was a siding between locks 2 and 3 but it was later extended to serve the pound between locks 1 and 2. The cutting for this siding from the main railway line can still be seen today and it is still in use by Network Rail to gain access to the line. The signal box controlling the junction was called Marple Wharf and it later controlled the branch going off to Rose Hill and Macclesfield. The wharf cost £1790 to construct, (about £220,000 today) and included a crane. The branch leading to the wharf consisted of a single track slip off the main line. It passed through the cutting and over Aqueduct Road (which at that time was the route of the tramway.)

Northern end of siding beside pound between Locks 1 and 2 is at SJ 95863 89951

Southern end of sidings just below Lock 3 is at SJ 96007 89837

Immediately beyond the road there were two sets of sidings, each adjoining a wharf beside a canal pound. The northern single siding was at a higher level than the canal and would be suitable for transhipping from rail waggon to canal barge. This was complemented by the southern two sidings which were below canal level so that the wagon floors would be about level with the wharf and the canal barge alongside. This would be suitable for transferring loads both ways. When it was decided to extend the life of the wharf and keep it working when the railway was completed, a house was built for the wharfinger on the opposite (towpath) side of the canal. Not only was he close to his work place and thus on call twenty four hours a day, but he also had an excellent view of all activiy on the wharf. Nothing would escape his notice. Today, although the house is long gone, the footprint of the foundations can still be made out if you know what to look for.

As the rail network expanded less traffic used the canal and the wharves gradually fell into disuse. The rail branch was removed in about 1900. The course of the branch is quite clear, even today, and the wharves are intact though overgrown. However there are few relics of Marple Wharf itself in clear view. In 1980 the remains of rotten sleepers and rusty iron work could be picked out amidst the bushes. Forty years on, they are probably still there, but nature has taken back its own and soon only the historical record will remain to tell us what once was there. However, the viaduct is still with us and going strong. Yes, it has had to be repaired, as can be seen by the use of engineering bricks on one of the central arches, but it remains a simple yet solid and dignified construction. It is as good now as when built in 1862 even though it is carrying trains many times heavier than those it was designed for. We should be proud of this viaduct in its own right, not merely as a backdrop to the aqueduct.

Words: Neil Mullineux

Map and some photos: David Burridge

Postscript

An occasional bonus can be gained when researching these articles by providing a link with another aspect of our history. So it was in this case. The main contractor for the viaduct was Benton and Woodiwiss, a reputable and well respected firm of railway contractors based in Derby. It was founded by two men from relatively humble backgrounds, George Benton and Abraham Woodiwiss. They both started their careers as stonemasons and prospered with the dramatic growth of the railways in the 1840s and 1850s. In 1861 they formed a partnership and took on contracts as principals rather than just as sub-contractors and the Marple viaduct was the first of their major contracts.

At the same time a Mary Woodiwiss was playing an important role in financing Hollins Mill. In the 1850s she had lent a total of £9000 to the Walmsley family, proprietors of Hollins Mill at that time. When the Carvers and the Hodgkinsons bought the mill in 1863 she lent them £10,000, well over one million pounds today, which was repaid to her five years later. In contrast to her namesake, Abraham, she was obviously a woman of some means. She had inherited the Hyde Hall estate from her father Francis in 1830 and he, in turn had purchased the same in 1813. She was also much older than Abraham as he was born in 1828 so they were not directly related. However, it is an unusual name and it would be fascinating to find out if there was any connection between the two, particularly as they both played a role in the history of Marple. Any offers?