We are the Marple Local History Society so you could not have a more local subject than Brentwood – an appropriate end to a memorable season. Brentwood and its residents were an integral part of Marple society for over thirty years and many visitors came to the meeting with experiences and anecdotes to relate. Michael Lambert shared some of his PhD research with us and, in return, we shared with him some of the atmosphere and anecdotes from those days more than half a century ago.

The house filled several roles in its time but the one common feature was its concentration on mothers with children. In its thirty three years, over 3,600 mothers came to stay for a shorter or longer period of rest and recuperation or reintegration into society. The regime tried to balance a recuperative element with appropriate vocational training against a background of changing controls, variable finance and continually changing staff.

The seeds of the institution wer e sown in the deepest part of the depression in the 1930s. The economy reached its nadir in 1933 but recovery was slow and there was widespread hardship. Various measures were taken to relieve the hardship but at first these were almost exclusively for men, not their wives. Gradually a few organisations began to offer facilities for women as it was recognised they were just as badly affected as the men, particularly because they bore the main responsibility for children. Brentwood became one of the first of these foundations when the Macnair family donated it anonymously in 1937. The family also made a contribution towards the running costs. The house itself on Church Lane had been built in 1884 and was lived in by several upper-middle class families before Andrew Macnair, a successful industrialist, bought it in the 1920s.

e sown in the deepest part of the depression in the 1930s. The economy reached its nadir in 1933 but recovery was slow and there was widespread hardship. Various measures were taken to relieve the hardship but at first these were almost exclusively for men, not their wives. Gradually a few organisations began to offer facilities for women as it was recognised they were just as badly affected as the men, particularly because they bore the main responsibility for children. Brentwood became one of the first of these foundations when the Macnair family donated it anonymously in 1937. The family also made a contribution towards the running costs. The house itself on Church Lane had been built in 1884 and was lived in by several upper-middle class families before Andrew Macnair, a successful industrialist, bought it in the 1920s.

Its original role was to give respite to women and children under severe pressure and the National Council for Social Service came to regard it as an exemplar. It was not the first large house to undertake that role –  there were a few others including Heathfield in Birch Vale – but it performed well in that capacity. However, when war came in 1939 it changed its function from being a holiday home to become a reception centre and temporary home for refugees, first from the Sudetenland (right) and then from the London Blitz.

there were a few others including Heathfield in Birch Vale – but it performed well in that capacity. However, when war came in 1939 it changed its function from being a holiday home to become a reception centre and temporary home for refugees, first from the Sudetenland (right) and then from the London Blitz.

By 1941 it changed yet again. The refugee emergencies were abating but the need to give ongoing or social respite was as strong as ever. The warden was seconded to open other centres around the country. Mrs Mary Macnair stepped in to provide some continuity until Doris Abrahams arrived to take over and lead the unit. She was fortunate in keeping a core of staff which provided stability throughout the rest of the war.

At the end of the war its role changed once again and for a decade it was a centre for problem families where the emphasis was to teach the mothers to be “better” housewives and mothers to their children. It was entirely voluntary for its visitors though a carrot and stick was used in persuading them to volunteer. A few attended as a condition of a probation order. Typically a woman would come for a period of four to six weeks, paid for by the local authority. Not all adapted easily and some left early; the shortest stay was under three hours.

A fixed programme was followed with classes in domestic skills - cooking, cleaning, sewing etc. leavened with organised relaxationsuch as dancing. Church attendance, though not obligatory, was encouraged on Sundays. The organisation of this programme was very hard work for the staff but the reputation spread. In 1948 it was mentioned in parliament for the work it was doing and there was a steady procession of international visitors.

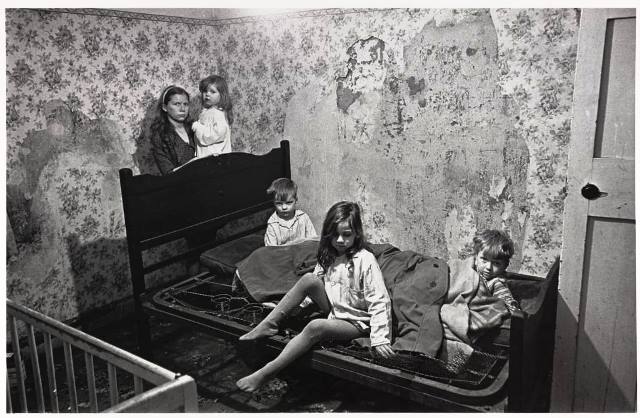

By 1953 conditions w Photograph by Nick Hedges. In 1968, Shelter employed Nick Hedges to document the oppressive and abject living conditions being experienced in poor quality housing in the UK. ere getting easier; postwar deprivations were easing, a local association “Friends of Brentwood” was formed and students came on a regular basis to carry out building and repair jobs. In 1957 an extension was opened and the next six years represented the high point in the organisation’s life. It influenced many other institutions around the country and abroad and was the subject of three case studies. Not that it was all smooth sailing. There were instances of theft and bad language, some husbands got drunk and got into affrays, but in everyday life Brentwood was an integral part of the community.

Photograph by Nick Hedges. In 1968, Shelter employed Nick Hedges to document the oppressive and abject living conditions being experienced in poor quality housing in the UK. ere getting easier; postwar deprivations were easing, a local association “Friends of Brentwood” was formed and students came on a regular basis to carry out building and repair jobs. In 1957 an extension was opened and the next six years represented the high point in the organisation’s life. It influenced many other institutions around the country and abroad and was the subject of three case studies. Not that it was all smooth sailing. There were instances of theft and bad language, some husbands got drunk and got into affrays, but in everyday life Brentwood was an integral part of the community.

However, this period did not last long. In 1963 the warden, Doris Abraham left after 20 years and with her departure the network of contacts around the country went too. A series of wardens staying for short periods succeeded her and, at the same time, both the law and social thinking changed. Local authorities had access to finance to set up their own homes and there was also a move towards keeping families in their own home rather than disrupting them. Brentwood began to receive the worst cases and husbands often accompanied wives, negating much of the progress that could have been made. Admission requirements were extended, raising the costs for applications. The combination of factors, all acting against Brentwood, led to a rapid decline. Within seven years the hostel proved unsustainable and it was closed on 1st November, 1970.

So what is there to show for over thirty years of providing a unique service to society? A block of flats was built within the grounds of Brentwood in the 1970s, suitably named Macnair Mews. Rather later, the house was demolished but the frontage retained and new apartments – Macnair Court – were built on the site. So, there is little in the way of physical artefacts but the Brentwood tradition lives on.

Neil Mullineux, April 2016

Two Brentwoods: Two Eras

Preston & Marple

The part of Lancashire County Council that was involved with Brentwood has gone through several transformations and is now known as “Community Futures” based in Preston. The activities have changed over time but the focus has always been on supporting, developing and sustaining communities. It is still performing that role from a Head Office at Brentwood House, Fulwood, Preston. The name lives on!